|

The phenomenology of Franciscan spirituality offers a profound exploration into the lived religious experiences derived from the life and teachings of St. Francis of Assisi, a significant figure in the Catholic Church. St. Francis, who lived in the 13th century, left a lasting legacy that has captured the hearts and minds of millions, grounding them in a spirituality marked by humility, poverty, simplicity, and a deep sense of communion with God and all of creation.

In the heart of Franciscan spirituality is the immediacy of the divine encounter. St. Francis’ life was marked by direct, pre-conceptual, and intimate experiences of God. His encounters were not mediated by elaborate theological constructs but were direct and immediate. From a phenomenological perspective, this is akin to an existential ‘givenness’ that manifests itself in and through the world, without the need for abstract reasoning or conceptual mediation. This immediate awareness of God, as phenomenology would suggest, constitutes the very essence of religious experience in the Franciscan tradition. Central to this spirituality is the embrace of poverty and humility. Francis, who renounced his wealth and lived amongst the poor, modeled a life that was not anchored in material possessions or social status. For Francis, true riches were found in a life that mirrored the humility and poverty of Christ. Phenomenologically speaking, this represents a radical ‘letting go’ of the ego and worldly attachments, allowing for an authentic, unmediated encounter with both God and others. In this light, poverty is not merely an absence of material wealth, but rather a profound self-emptying—a kenosis—that creates space for the divine to enter and transform one’s life. Closely tied to the embrace of poverty and humility is Franciscan spirituality’s emphasis on fraternity and communal living. Inspired by St. Francis, the Franciscan orders are structured as brotherhoods, reflecting a deep and abiding sense of community. In phenomenological terms, this suggests a fundamental intersubjectivity at the heart of human experience. Franciscan spirituality posits that individuals are deeply interconnected with others and are called to live in harmonious, loving relations, thereby fostering a profound sense of the ‘other’ as not separate, but intimately related—a true brother or sister. Furthermore, Franciscan spirituality is renowned for its deep love and care for creation, as evidenced in the famous Canticle of the Sun by St. Francis, where he refers to the sun, moon, and earth as his brothers and sisters. Phenomenologically, this reflects a non-dualistic stance towards the world, wherein the divine is perceived as immanently present in all aspects of life. This perspective invites a stance of reverence and stewardship towards all of creation, recognizing the interconnectedness and sacredness of all life forms. A distinguishing feature of Franciscan spirituality is the harmonious balance it maintains between contemplative prayer and active service. This spirituality is not solely an inward, contemplative gaze towards the divine; it is also an outward, active gaze towards the world in need. Phenomenologically, this reflects the dynamic, reciprocal movement of consciousness that is both receptive (contemplative) and active (engaging with the world in love and service), mirroring the divine love that is simultaneously immanent and transcendent. In conclusion, the phenomenology of Franciscan spirituality provides a rich and textured lens through which to understand the profound and transformative path towards union with God and harmony with the world as inspired by St. Francis of Assisi. It is a path marked by immediate awareness of the divine, a commitment to poverty and humility as means of liberation, a deeply communal and fraternal way of life, a reverence for and communion with all of creation, and a harmonious integration of contemplative depth with active, loving service. Through the lens of phenomenology, the lived experience of Franciscan spirituality emerges as deeply embodied, relational, and transformative, offering a compelling and authentic way to live out the Christian journey.

0 Comments

In the realm of classical music, Erik Satie’s piano compositions exist as idiosyncratic whispers, challenging our quotidian perceptions of sound, rhythm, and musical narrative. From a phenomenological standpoint, engaging with Satie’s works is akin to immersing oneself in a complex auditory tapestry; a blend of sonic manifestations and silences, inviting listeners into a vivid world of musical phenomena.

Satie, ever the ‘gymnopedist’ and ‘phonometrographer’, crafts his compositions as spaces where the phenomenon of sound is both exposed and enigmatic. In his iconic Gymnopédies and Gnossiennes, there is a conspicuous absence of the lavish ornamentation characteristic of his contemporaries. Instead, Satie presents us with a stark, unembellished soundscape, which phenomenologist Maurice Merleau-Ponty might describe as a direct, ‘pre-reflective’ experience of sound, unhindered by excessive theoretical or structural baggage. In Satie’s piano works, one can discern an exploration of Husserl’s concept of ‘epoche’ - a suspension of the natural attitude, inviting listeners to engage with the music in a pure, unmediated manner. His repetitive, almost hypnotic motifs, as in Ogive No.1, facilitate a bracketing of expectations. Listeners are ushered into a space where familiar temporal and harmonic constructs are made strange, encouraging a focus on the ‘phenomena’ of the notes themselves, rather than their functional roles within a broader harmonic narrative. The sparse texture and deliberate pacing of Satie’s compositions serve as an invitation to the ‘intentionality of consciousness’ - a central theme in phenomenology. Each note, in its stark isolation, becomes a ‘noema’, an object correlated with our conscious experience, facilitating a profound sense of engagement and reflection. In this musical space, sound and silence are not binary opposites, but rather intertwined elements of a singular, unfolding phenomenon. Satie’s use of space and silence is as deliberate and impactful as his notes, encouraging listeners to dwell in these ‘horizons of absence’ as meaningful components of the auditory experience. Furthermore, Satie’s notations on his scores, often whimsical and seemingly irrelevant to the music, can be seen as a nod to Heidegger’s notion of ‘Dasein’, or ‘being-in-the-world’. These instructions do not dictate the technical aspects of performance but rather suggest a particular mode of ‘being’ within the world of the composition. For example, his direction to play certain passages ‘like a nightingale with a toothache’ in Embryons desséchés subverts the traditional performer-text relationship, situating the pianist, and by extension the listener, as a participant in a shared, evolving musical narrative. In conclusion, Erik Satie’s piano works, when approached phenomenologically, emerge as complex, textured realms of experience. They invite us to engage deeply with the phenomena of sound and silence, to suspend our habitual modes of listening, and to inhabit a world where musical notes are not mere symbols on a page, but vibrant, pulsating entities in a rich and ever-unfolding tapestry of consciousness. Satie’s compositions are, in essence, an invitation: to listen, to reflect, and to be within the manifold layers of sound and absence, where music becomes a profound act of phenomenological inquiry. I consider myself a philosopher as much as a musician. My research primarily focuses on a phenomenological approach to music, especially with the self-awareness that music lies within a spatial and temporal framework. This chapter will specifically detail my research interests as a philosopher, not necessarily giving you a breakdown of my research, but outlining the broad topics of which I believe is most important. Philosophy seeks to ask questions, and I would encourage you not to simply read my thoughts, but ask questions about what you are listening to, why you are experiencing different things, and how this can foster a deeper interest, understanding and love for music. Saying this, I am going to be broadly speak from a phenomenological standpoint; this is a branch of philosophy that is concerned with the nature of consciousness and the structure of subjective experience. At its core, phenomenology is concerned with questions such as: What is the nature of subjective experience? How do we perceive and understand the world around us? What is the relationship between consciousness and the world? In relation to music, phenomenology can be used to explore the ways in which music shapes and is shaped by subjective experience. For example, phenomenologists might examine the ways in which music evokes strong emotions, creates a sense of meaning and significance, or shapes our perception of the world around us. Throughout the history of philosophy, there have been many philosophers who have explored the intersection of phenomenology and music. From Edmund Husserl, who is considered the founder of phenomenology, to Jean-Luc Nancy and Don Ihde, who have examined the role of music in shaping and being shaped by subjective experience, the relationship between phenomenology and music is a rich and complex one.

Phenomenological spatiality is a concept that refers to the ways in which our perception of space and spatial relationships shapes and is shaped by our subjective experience. In contrast, temporality refers to how our perception of time shapes our consciousness. Looking at both musical spatiality and temporality from a phenomenological standpoint can be seen as how our perception of temporal relationships influences our consciousness and experience while listening to music. One philosopher who has explored the concept of phenomenological spatiality, temporality and it’s relation to music (and sound in general) is Jean-Luc Nancy. Nancy has argued that music has the ability to create a sense of "sonorous space and time” that shapes our experience of the world. He believes that music has the power to evoke a sense of spatial presence and to create a sense of "sonorous depth and duration” that allows us to experience the world in a new and meaningful way. In a similar way to Nancy, Don Ihde has argued that music has the ability to create a sense of environment and flow that shapes our experience of the world. He believes that music can create a general sense of spatial awareness immersion. This self-awareness that comes with consuming music often leads to a greater self-consciousness, which can often teach us not only about the music, but about ourselves and the world around us. There have also been a number of composers who have explored the concept of phenomenological spatiality in their music. One example is John Cage, who is known for his experimental and avant-garde approach to music. A pioneer of music as ‘experiments’ (experimental music), Cage believed that music had the power to create a sense of "sonorous space" that shaped the listening experience, and he often used unconventional musical structures and techniques to evoke this sense of spatial presence. So, what actually is time? From a purely scientific point of view, time is a fundamental aspect of the universe and is closely linked to the concept of space. Time is often thought of as a measure of the duration of events, and it is usually measured in units such as seconds, minutes, and hours. In classical physics, time is considered to be an independent variable that can be measured objectively and that is independent of the observer. This means that time is thought to be a universal quantity that is the same for all observers, regardless of their location or frame of reference. In modern physics, time is still considered to be an important aspect of the universe, but its nature is more complex and nuanced. According to some theories in modern physics, such as relativity and quantum mechanics, the concept of time is closely linked to the concept of space, and the two are considered to be part of a single unified entity known as spacetime. In these theories, time is still thought to be a measure of the duration of events, but it is also thought to be affected by the presence of matter and energy, and by the curvature of spacetime. As a result, time is not considered to be an objective and universal quantity in the same way that it is in classical physics. However, time in relation to the consciousness is vastly different. The consciousness does not just take the idea of time at face value, rather our experience enhances it, moulds it and makes it wholly subjective to our own consciousness. There is an important distinction and fundamental difference between space and time that should be made. Space is something where you can move around; if I want to go to see a music concert, I will physically take myself to a concert hall. However, if I want to see a concert that happened three-hundred years ago, I cannot move around in time in the same way I can in space. However, when I move in space, I cannot do so without moving in time; time will always be moving ‘forward’ (or, at least, a clock will always be moving forward). It is difficult to both separate and join these two elements of the universe (or of consciousness, depending on your philosophical standpoint). Yet, often they are seen as two sides of the same coin. One way to understand the relationship between space and time is through the concept of spacetime. Spacetime is a framework that combines space and time into a single, unified entity. This concept was first proposed by Hermann Minkowski in 1908 and has since become a cornerstone of modern physics. According to the theory of relativity, the concept of spacetime is necessary to understand the nature of the universe. According to this theory, the laws of physics are the same for all observers, regardless of their relative motion. This means that the passage of time can appear different to different observers, depending on their relative speed. For example, time appears to move slower for an observer moving at a high speed compared to an observer at rest. This phenomenon, known as time dilation, is a direct consequence of the curvature of spacetime. In addition to time dilation, the theory of relativity also predicts that the fabric of spacetime can be distorted by the presence of matter and energy. This phenomenon, known as spacetime curvature, is what causes objects to experience gravity. In other words, the gravitational force experienced by an object is a result of the way that its motion is influenced by the curvature of spacetime caused by the presence of other masses. The relationship between space and time can also be understood in terms of the concept of symmetry. Symmetry is a property of a system that remains unchanged despite certain transformations. One example of symmetry is the rotational symmetry of a circle, which remains unchanged no matter how it is rotated. The concept of symmetry is relevant to the relationship between space and time because it suggests that the laws of physics should be the same in all inertial frames of reference. In other words, the laws of physics should not depend on the relative motion of the observer. This idea is known as the principle of relativity, which is a cornerstone of the theory of relativity. Symmetry, temporal dilation and other scientific concepts tell us about the objective world, but may not enlighten us much about how we experience music, and how space and time affects us when consuming or creating music. Nevertheless, I believe it is helpful to understand the scientific foundations of the temporal and spatial to understand how we can approach these things in relation to our consciousness. Furthermore, these things are not mutually exclusive. Science and philosophy are two different ways of understanding the world. Science is a systematic and logical approach to discovering new knowledge about the natural world, based on empirical evidence and experimentation. Philosophy, on the other hand, is a more abstract and theoretical pursuit that involves questioning fundamental assumptions and concepts, such as the nature of reality, existence, knowledge, and value. Both science and philosophy have something valuable to contribute to our understanding of time and space. Science helps us to understand the physical properties of time and space and how they behave according to the laws of physics. Philosophy, on the other hand, helps us to understand the conceptual and metaphorical aspects of time and space and how they relate to our experience of the world. It is much like, in the Christian faith, having an idea of Jesus Christ and knowing Jesus Christ in the relational sense. We can have an deep intellectual idea of who Christ is, what He does and how he works in our lives, but it is the act of self-investigation from a philosophical standpoint that draws us to deeper truths about ourselves and the world around us. Having both a scientific and philosophical understanding of time and space can also help us to bridge the gap between the two approaches and to see the connections between them. For example, science can inform our philosophical understanding of time and space by providing empirical evidence and testable theories, while philosophy can help us to understand the broader implications and meanings of scientific concepts. However, most importantly, the both complement each other by raising opposite questions. If I were to ask a question about how the temporal fabric of the universe is structured, this will naturally lead me to questions of why this is. In a similar way, if I ask myself if space has any inherent meaning, or whether it is just a backdrop for events to unfold, I will be forced to ask questions about the physical and scientific fabric of space. Saying this, I am no scientist, and have a deeper interest in philosophy. Therefore, I am interested in asking philosophical questions about music. Thus, if we have a philosophical awareness when creating and consuming music, we are actively encouraged to ask ourselves specific questions about experience and our consciousness; where might concentration lie? How might we perceive sound? What emotions might we feel? For music creators, if a phenomenological approach is present in the music writing process, then there is both a dynamic relationship between the composer and listener and a vested subjectivity in the conception of the musical idea along with the piece’s subsequent architecture. My current musical interests lie in the unfolding of the combinatorial process over time that results in a static sound world. When listening and reflecting on my music, I have found that the experience of narrative does not lie in ‘the music itself’. Rather, the experiential chronology lies in the way that the listener perceives repetition, experiences the flexing of time and the fluctuation in their concentration. At one point in the music, their attention may be focused deep into the chronology and development of the enumeration but may shift to another extreme, not even focusing on the fact they are listening to music. To have an awareness of the temporal implications of the music during the compositional process would be to engage with phenomenology; to understand that the experience of time passing is both momentary and personal to every individual listener. Although there may be fortuitous events that create changes in this experience as something personal, such as extraneous sound from the concert hall or the physical eccentricities of a performance, many composers who engage with statis in their work naturally display phenomenological awareness. Static music naturally lacks teleology; the narrative of musical experience is not engraved in the score. Instead, the narrative (or at least, chronology) is transferred to the listener, made up of momentary experience where one might zoom in and out of a score, observing minute details in the sound or being more aware of the physicality of the space the music is being performed in. There are times at which one may argue there is objectivity in the surprising elements of musical composition. However, the listener’s perception of what is fortuitous is still affected by their experience and character. Furthermore, these surprises are always characterised as ‘moments’ which is, in itself, problematic. The German philosopher Edmund Husserl talks about “immanent time”, describing the moment as only possible within a focal-point. From a phenomenological perspective, the experience of time passing is not only a subjective experience but unique to an individual, shaped by the person’s characteristics and eccentricities. David Clarke suggests that this is in part due to there being an ambiguity in momentary experience. He asks the question in the book Music and consciousness “how do we make a robust distinction between the moment of perception and the beginnings of memory?” If a composer has an awareness of phenomenology, especially when investigating temporal implications of musical perception, it seems that on any level, time perception has an innate fluidity. Each listener’s levels of perception may differ within a piece of music. Furthermore, even if a listener is fully engaged with a particular element of the music at a point in time, the perception of that moment may not be distinct due to the obscurity between the experience of the present and recollection. In 2021, I wrote this short commentary for a piece of music I composed for piano, called ‘Slowing up and speeding down’. As probably guessed, the work plays on the listener’s awareness of their temporal consciousness, as the music is static and unchanging throughout so is their attention, which begins to drift and the musical narrative forms within their own consciousness rather than within the music itself. Listening 'at this moment in time is much like a dog chasing its tail. When a listener hears and subsequently directs their attention to a moment, they are merely examining a memory. If one anticipates a moment and focuses on a time-point, they are merely pre-empting a moment. Many may describe temporality as linear experience; left to right, right to left, or a continuous line stretching to and from eternity. However, temporality operates in absolute parallel with spatiality. I see time as something which comes at and over you. Occasionally, you may be looking forward and observing a time-point approaching you. At other times, you may be looking behind you and witnessing a time-point fade into the infinite distance. The past and future are strong forces constantly fighting to grab your attention. Perhaps you could look up? Much like a cloud flies high above your head, the time-point at which the raindrop leaves the cloud compared to when it hits your head sits in a different place on the temporal spectrum. What may feel like the present is often the past and, if not, a murky anticipation of a time-point. Although a real-world moment and a moment as a manifestation of our consciousness are different, what qualities does a real-world moment have? How do we interact with a time-point when we experience it? The primary stage of experiencing a moment in time is our delayed experience to a real-world time-point. We often use terms such as 'immediate' or 'present' to describe this. Real-world moments are indestructible, but often our consciousness is shrouded in time-points that these time-points present as decaying objects as time passes over us. There is a direct correlation between the distances separating us from our delayed experience of a time-point and the perceived decay of a time-point experience. This decay will eventually present as nothingness but a false nothingness. A period of temporal experience may follow where the initial experience of the time-point presents as nothingness but may appear again as a memory. This memory has very little to do with the fixed real-world time-point but is a false manifestation of the time-point experience. Both the time-point experience and the memory are not bound by the real-world temporal spectrum and so cannot be classified as a moment. Moments occur in the real world and are present as time-points, not in the consciousness. However, human consciousness acts as a barrier between the real world and our apprehension of a time-point. A moment in temporal consciousness may present as either a loose-fitting observation of a time-point approaching us, a decaying time-point experience or a severely injured time-point manifesting as a memory. The final concept I am going to talk about is memory. As one may gather from these writings above, I hold a vastly different view on the existence of the future in comparison to the past (and present, for what it’s worth). The past is a tangible thing which we can internalise in our consciousness; we have memories and recollections which can influence our emotions from present stimuli. However, the future is something which we have no certainty about. We can anticipate and predict, but these thoughts are completely defined by our past and present experience. In my opinion, if we are to argue of the fabric existence of the past, present and future in relation to our consciousness, only the first two would have any merit for a philosophical arguments.From a philosophical standpoint, memory is typically seen as a central aspect of human cognition and is closely related to other mental states and processes such as perception, attention, and learning. There are many different philosophical approaches to the concept of memory, and there is ongoing debate about its nature, function, and limitations. Some philosophers see memory as a kind of mental representation or record of past events, while others see it as a more active process of reconstruction and interpretation. This debate has important implications for how we understand the reliability and accuracy of memory, as well as its potential for distortion and manipulation. Another key aspect of the philosophy of memory is the relationship between memory and personal identity. Many philosophers argue that our memories are an integral part of who we are, and that they shape and define our sense of self. Others, however, argue that our sense of self is more fluid and dynamic, and that it is not necessarily tied to our memories. When thinking about music, there is a clear link between our memory and the emotional response that we may have from encountering music. This can both be from hearing music that reminds us of something, or from reoccurring themes and developments within the same piece of music. There is a philosophical concept called Rilkean memory, which can be separated into two strands; embodied and affective. Embodied memory consists of behavioural and bodily forms, while affective memory deals with emotions, moods and feelings. A Rilkean memory begins when a regular memory becomes fragmented or lost. For example, you may hear a piece of music at a funeral. If you hear the piece of music again, although you may not remember that you once heard it at a funeral, it may bring about a Rilkean memory in its affective form, which creates an emotional response, even when that autobiographical memory of the music is lost. The relationship between both memory and emotions are extremely complex, however, there seems to be two important points to make here. Firstly, memories are often accompanied by emotions. These may either be part of the memories themselves, or be an emotion directed at the memory of an event. Secondly, there are certain emotions that are only present with memories. For example, nostalgia, regret, guilt, and remorse are all present only when a memory is present. This means that, in relation to music, we can think of times in which an listener can feel an emotion to something in relation to another musical event which arises solely from a memory. However, this raises the question as to whether these emotions are felt in relation to the memory itself, or whether it should be understood as circumstantial. In any case, considering the philosophical idea of memory is important when appreciating music because it can deepen our understanding and appreciation of the music itself, as well as the experiences and emotions it evokes. Memory allows us to contextualize the music and connect it to our personal histories and emotions, which can enrich our experience of listening to it. Additionally, thinking about the nature of memory and how it shapes our experience of music can also lead us to reflect on the role that memory plays in our lives more broadly, and how it shapes our understanding of the world around us. Overall, engaging with the philosophical idea of memory when appreciating music can enhance our enjoyment of the music and also promote deeper self-reflection and understanding. Fundamentally, thinking about music from a philosophical standpoint can be a powerful tool for enhancing our appreciation of music and using it in our daily lives to promote positive mental and physical health. By considering the various philosophical ideas and concepts that are related to music, such as aesthetics, emotion, and meaning, we can gain a deeper understanding of the music we listen to and how it affects us. This, in turn, can help us to more fully engage with the music and derive greater enjoyment from it. Moreover, thinking about music from a philosophical perspective can also help us to use music more intentionally and effectively in our daily lives. For example, we can choose music that aligns with our values and goals, and use it to help us focus, relax, or motivate ourselves. We can also consider how different musical styles or traditions reflect different cultural and historical contexts, and use this understanding to expand our musical horizons and enrich our lives. In addition to the personal benefits of thinking about music from a philosophical standpoint, such as increased enjoyment and self-awareness, doing so can also have broader social and cultural benefits. By engaging with music in a more thoughtful and reflective manner, we can foster greater understanding and appreciation for diverse musical traditions and the people who create and perform them. This can help to build bridges of connection and understanding between people of different backgrounds and experiences, and contribute to a more harmonious and inclusive society. Overall, thinking about music from a philosophical standpoint is an important and rewarding way to enhance our appreciation of this rich and multifaceted art form, and to use it more effectively and positively in our daily lives. By considering the various philosophical ideas that are relevant to music, we can deepen our understanding and enjoyment of it, and use it as a source of inspiration, relaxation, and personal growth. The concept of cyclic temporality is a central aspect of baroque music, with many of the composers of the period using cyclic structures to create a sense of continuity and coherence in their music. This approach to musical form is particularly evident in the work of composers such as Johann Sebastian Bach and George Frideric Handel, who use cyclic structures to create a sense of narrative and development in their music.

One of the key features of cyclic temporality in baroque music is the use of recurring musical ideas and themes. In many cases, these themes are introduced at the beginning of a piece and are then repeated throughout the course of the work, creating a sense of continuity and coherence. This is particularly evident in Bach's keyboard suites, in which he uses recurring themes and motifs to create a sense of narrative and development. The concept of cyclic temporality in baroque music is closely linked to philosophical theories about consciousness and phenomenology. According to phenomenological theories, consciousness is characterized by a sense of temporal flow and development, with each moment arising from and giving rise to the next. This idea is reflected in the music of the baroque period, in which composers such as Bach and Handel use cyclic structures to create a sense of continuity and coherence. Furthermore, the use of cyclic structures in baroque music can be seen as a reflection of the way in which consciousness itself is structured. According to some philosophical theories, consciousness is characterized by a series of recurring themes and motifs, which are constantly repeated and re-shaped in response to the changing world around us. This idea is reflected in the music of the baroque period, in which composers use cyclic structures to create a sense of narrative and development. For example, in Bach's Prelude from his first keyboard suite (Well Tempered Clavier, Book 1, Prelude No. 1 in C Major), the opening theme is repeated throughout the piece, creating a sense of continuity and coherence. This theme is first introduced in the opening measures of the piece, and it is then repeated in various forms throughout the rest of the composition. Through this use of repetition, Bach is able to create a sense of narrative and development, with the music continually moving forward and unfolding in response to the recurring theme. The use of cyclic structures in baroque music is also closely linked to the concept of narrative. Many of the composers of the period use cyclic structures to create a sense of narrative progression, with the music continually moving forward and unfolding in response to the recurring themes and motifs. This is evident in the work of Handel, who uses cyclic structures to create a sense of drama and tension in his music. For example, in Handel's Largo from the opera Xerxes, the composer uses a cyclic structure to create a sense of narrative progression. The piece begins with a simple, repeated bass line, which establishes a sense of continuity and coherence. Over the course of the piece, Handel introduces various melodies and harmonies that are built upon this repeated bass line, creating a sense of development and forward momentum. Through this use of cyclic structures, Handel is able to create a sense of narrative and development in the music. Furthermore, the use of cyclic structures in baroque music can be seen as a reflection of the way in which consciousness itself is structured. According to some philosophical theories, consciousness is characterized by a series of recurring themes and motifs, which are constantly repeated and re-shaped in response to the changing world around us. This idea is reflected in the music of the baroque period, in which composers use cyclic structures to create a sense of narrative and development. Overall, the use of cyclic temporality in baroque music is a key aspect of the compositional style of the period. Through the use of recurring themes and motifs, composers such as Bach and Handel are able to create a sense of continuity and coherence in their music, and they use these structures to create a sense of narrative and development. This approach to musical form is a key feature of baroque music, and it continues to be a source of inspiration for composers to this day. The use of temporality in the symphonies of Jean Sibelius is a central aspect of his compositional style. Throughout his symphonic works, Sibelius explores the complex relationship between time and music, and he uses a range of compositional techniques to create a sense of temporal flow and development.

One of the most notable ways in which Sibelius uses temporality in his symphonies is through his use of extended musical forms. In contrast to the traditional symphonic form, which is typically structured around a series of repeated musical ideas and clear-cut structures, Sibelius's symphonies are often characterized by a sense of openness and indeterminacy. Rather than following a predetermined form, the music in his symphonies is often structured around a series of temporal events, with each event unfolding in its own unique way. This approach to musical form is evident in many of Sibelius's symphonies, including his fifth and seventh symphonies. In both of these works, Sibelius uses extended forms to create a sense of temporal flow and development, with the music continually shifting and evolving in response to the temporal structures that he has created. This creates a sense of dynamic movement, as the music continually unfolds and changes in response to the temporal structures that Sibelius has created. In addition to his use of extended forms, Sibelius also employs a range of other compositional techniques to create a sense of temporality in his symphonies. One of these is his use of repetition, which he employs in a number of different ways throughout his symphonies. In some cases, Sibelius uses repetition to create a sense of continuity and coherence, as the music continually returns to familiar musical ideas and structures. In other cases, he uses repetition to create a sense of instability and uncertainty, as the music continually shifts and changes in response to the repeated material. Another key aspect of Sibelius's approach to temporality is his unique use of the orchestra. Throughout his symphonies, Sibelius employs the full range of orchestral colors and textures, using the various instruments of the orchestra to create a sense of temporal flow and development. This is particularly evident in his seventh symphony, in which Sibelius uses the orchestra to create a sense of dynamic movement, with the music constantly shifting and changing in response to the various instruments of the orchestra. Overall, the use of temporality in the symphonies of Jean Sibelius is a central aspect of his compositional style. Through his innovative approach to musical form and his use of repetition and the orchestra, Sibelius is able to create a sense of temporal flow and development that is both dynamic and engaging. His symphonies are a testament to his mastery of the art of symphonic composition, and they continue to captivate and inspire listeners to this day. Morton Feldman's Triadic Memories is a landmark composition in the history of contemporary classical music. Commissioned by the pianist Ursula Oppens and premiered in 1981, the piece is a striking example of Feldman's distinctive compositional style, which is characterized by a focus on temporal structures and the use of extended musical forms.

At the heart of Triadic Memories is Feldman's innovative approach to musical form, which is centered around the use of temporal structures. Unlike traditional musical forms, which are typically based on the repetition of musical ideas and the use of clear-cut structures, Feldman's approach is much more open-ended and fluid. Rather than following a predetermined form, the piece is structured around a series of temporal events, with each event unfolding in its own unique way. The result is a piece that is characterized by a sense of unpredictability and indeterminacy. As the music unfolds, the listener is constantly surprised by the unexpected turns and twists that the piece takes, with the music continually shifting and evolving in response to the temporal structures that Feldman has created. This sense of surprise and uncertainty is a key feature of Feldman's music, and it is one of the things that makes Triadic Memories such a striking and original composition. One of the most notable aspects of Triadic Memories is the way in which Feldman uses the piano to create a sense of temporal flow. Throughout the piece, the piano plays a central role, with the music constantly shifting and changing in response to the pianist's movements. This creates a sense of dynamic movement, as the music continually evolves in response to the pianist's touch. Feldman's use of the piano in this way is a key element of his compositional approach. By using the piano as the primary source of musical material, he is able to create a sense of temporal flow that is uniquely suited to his compositional style. This approach is evident throughout Triadic Memories, as the piano plays a central role in shaping the course of the piece. In addition to his use of the piano, Feldman also employs a range of other techniques to create a sense of temporal flow in Triadic Memories. One of these is his use of extended musical forms, which allows the music to unfold over long periods of time. This creates a sense of continuity and coherence, as the music flows seamlessly from one moment to the next. Another key aspect of Feldman's approach is his use of repetition, which he employs in a number of different ways throughout the piece. In some cases, he uses repetition to create a sense of continuity and coherence, as the music continually returns to familiar musical ideas and structures. In other cases, he uses repetition to create a sense of instability and uncertainty, as the music continually shifts and changes in response to the repeated material. Overall, Feldman's use of temporal structures in Triadic Memories is a key element of his compositional approach. By using extended forms, repetition, and the piano to create a sense of temporal flow, he is able to create a piece that is both unpredictable and engaging. Through his innovative approach to musical form, Feldman has created a work that is truly unique and original, and that continues to captivate and inspire listeners to this day. What defines our western society? To me, it often feels like capitalism and consumerism. What does it mean to create art in a capitalist society? We often consider artistic merit, authenticity and the value of art. However, these three things are easily exploited and commercialised, making them the opposite of what they are, much like how the individual worth of mass music 'itself' becomes mass worth and profitability).

Capitalism aims to turn art into a commodity. The characteristic of a commodity is to monetise an object whereby its value is only in relation to everything else within the marketplace. If you put a price on these things, their value is only worth their price. What is the value of a sheep as a food source versus as part of a picturesque view? The fundamental issue here is that the commoditisation of art offers no consideration of individual value or the value of its production, human labour or collaborative/community efforts. This commodification of value will inherently create a division of authorship between the consumer and the art. Furthermore, capitalism seeks to exploit art as an industry. Art, or the presentation of art through media and advertising, is being produced for the marketplace. The issue is that the art follows a set of conventions based on mass culture because we understand what the consumer wants. This creates a dialectical process between the art and the consumer; the idea of value becomes a dialogue between the value of human creativity and the price it will sell for. A critical factor in this commoditisation is the introduction of recording and streaming technologies. Reproduction itself is not necessarily a bad thing. In music, we have pastiche writing. In fine art, we have imitation. Both processes take skill and may enhance the artist's skill, supposedly increasing the value of further art produced at an individual level. Reproduction can also produce imperfections which can hold inherent value to the audience on an individual basis. Reproduction can be both a form of art and art itself; photography is entirely based on this principle. There is no 'original work', rather a reproduction and heavily distorted representation here. Therefore, why is art that is produced and then reproduced in mass a problem? Imagine there are two tables, one hand-made by a carpenter and one mass-produced from a multi-national furniture store. Instinctively, we may say that the former has more inherent value - but why? In the ready-made table, the object's form is not inherently from the designer's creativity but rather the analytical perception and assumption of aesthetics based on capitalist reasoning. Perhaps it is the perception of individual ownership that the object makes the receiver experience a sense of uniqueness, a process whereby an object may be seen as an extension of who you are. It is a good thing when an artist has a philosophical awareness. The value of art is dialectical; how does an artist or consumer see the concept of price besides the value of human work? By engaging with philosophical ideas their art poses, artists can try to resolve this tension and go beyond these conflicting terms to reach something new, a common objective of art creation. Listening 'at this moment in time is much like a dog chasing its tail. When a listener hears and subsequently directs their attention to a moment, they are merely examining a memory. If one anticipates a moment and focuses on a time-point, they are merely pre-empting a moment. Many may describe temporality as linear experience; left to right, right to left, or a continuous line stretching to and from eternity. However, temporality operates in absolute parallel with spatiality. I see time as something which comes at and over you. Occasionally, you may be looking forward and observing a time-point approaching you. At other times, you may be looking behind you and witnessing a time-point fade into the infinite distance. The past and future are strong forces constantly fighting to grab your attention. Perhaps you could lookup? Much like a cloud flies high above your head, the time-point at which the raindrop leaves the cloud compared to when it hits your head sits in a different place on the temporal spectrum. What may feel like the present is often the past and, if not, a murky anticipation of a time-point.

Although a real-world moment and a moment as a manifestation of our consciousness are different, what qualities does a real-world moment have? How do we interact with a time-point when we experience it? The primary stage of experiencing a moment in time is our delayed experience to a real-world time-point. We often use terms such as 'immediate' or 'present' to describe this. Real-world moments are indestructible, but often our consciousness is shrouded in time-points that these time-points present as decaying objects as time passes over us. There is a direct correlation between the distances separating us from our delayed experience of a time-point and the perceived decay of a time-point experience. This decay will eventually present as nothingness but a false nothingness. A period of temporal experience may follow where the initial experience of the time-point presents as nothingness but may appear again as a memory. This memory has very little to do with the fixed real-world time-point but is a false manifestation of the time-point experience. Both the time-point experience and the memory are not bound by the real-world temporal spectrum and so cannot be classified as a moment. Moments occur in the real world and are present as time-points, not in the consciousness. However, human consciousness acts as a barrier between the real world and our apprehension of a time-point. A moment in temporal consciousness may present as either a loose-fitting observation of a time-point approaching us, a decaying time-point experience or a severely injured time-point manifesting as a memory. Full review can be found here: http://www.larkreviews.co.uk/?cat=3

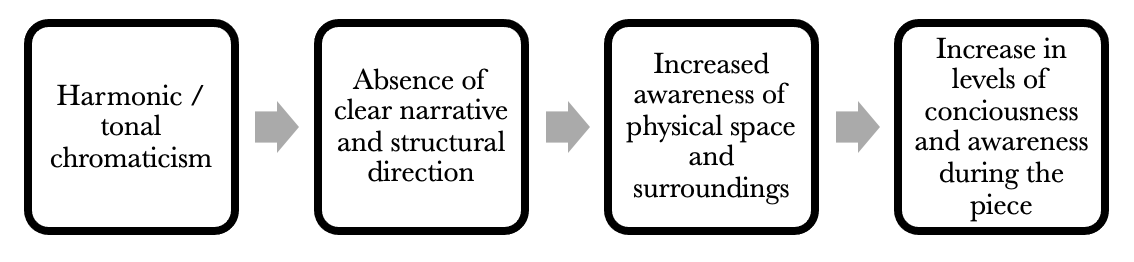

In 1871, Queen Victoria opened the Royal Albert Hall to pay tribute to her late husband, Prince Albert. This morning’s BBC Proms concert pays homage to the opening seasons of 1871 and 1880 with music inspired by the opening concerts almost 150 years ago. Sitting on the organ bench today was Westminster Abbey’s (previously St Paul’s Cathedral’s) sub-organist, Peter Holder. However, Holder is not new to the proms; his first debut was in 2019, where he performed Janá?ek’s Glagolitic Mass on its opening night. The concert opened with Giacomo Meyerbeer’s Coronation March from his grand 1849 opera Le prophète. While listening to this stately march, I found myself lamenting that Meyerbeer’s operas are rarely performed nowadays. Nevertheless, with all of the organ stops drawn out, I was moved by the works imperial and palatial character. No organ recital is complete without J.S. Bach, or so they say. Bach’s Fantasia and Fugue followed in a more reposed style. Holder chose a combination of quieter stops for the Fantasia, which was highly effective; it allowed one to adjust oneself to the complex eccentricities of Bach’s complex contrapuntal writing. Moving forward 200 years, Charles-Marie Widor’s Allegro Vivace from his Symphony No. 5 followed. Most may recognise the infamous final toccata movement, notably played at weddings during the bride’s departure. However, Holder executed this opening movement with dynamism and vigour. His agility shone mid-way through where he drew the organ’s flute stops demonstrating Widor’s delicate but tortuous melodic writing. The work ends with a triple f, or ‘as loud as you can go’. Colloquially, the organist is forbidden to draw all of the stops at once at the Royal Albert Hall, as it is said to damage the brickwork due to the vibrations! Now, onto what I was most looking forward to hearing; the Fantaisie No. 1 in Eb by the French 20th-century composer Camille Saint-Saëns. The Albert Hall organ was built in a ‘British orchestral’ style and is thus not commonly suited to French romantic organ music with heavy French diapasons and nasal reeds. Nonetheless, Holder performed the music of this centenary composer with much deftness. The highlight of this piece was the cadenza passage before the final few chords, where each hand plays the same notes by an octave apart. With the Albert Hall’s considerable acoustic, Holder managed to articulate every note so that the audience could precisely hear what Saint-Saëns had to say. The final work in the programme was Franz Liszt’s infamous work Fantasia and Fugue on the plainchant ‘Ad nos, ad salutarem undam’. The longest piece in the programme by a whole 20-minutes, this work was best saved to the end. Often considered one of the most challenging works in the organ repertoire, with its fast-changing harmonic progressions and dexterous melodic runs, Holder performed the piece with an incredible amount of ingenuity. The work has passages that are much akin to the organ writing of Charles-Marie Widor, whom we heard earlier, and the aesthetic of the two composers placed in the same programme created a noticeable synergy. Before the work ends, Holder managed to show off the organ’s Tuba Mirabilis stop, the loudest solo stop on the organ. Overwhelmed by the turbulence of the sound, Holder received a much-deserved standing ovation, followed by an invitation from the audience to play an encore, which he unfortunately declined. What an extraordinary end to the concert; I am sure that this will not be the last time we see Peter Holder at the BBC Proms over the coming years! Prior to Edmund Husserl’s 1913 publication Ideen, the transcendental and idealist philosophies of Immanuel Kant onwards were centralised around independence and self-awareness. A focus on self-consciousness was also a concern of composers writing during the beginnings of music as an experimental discipline, which Jenny Gottschalk argues that “the focus (in experimental music) is ontological, on being in that collective space and what transpires in the place and time of the performance, and in the minds of those who attend”. (Gottschalk 2016) Phenomenological qualities such as temporal awareness and fluctuating attention are the primary concern of many composers today, but can be traced back to composers writing at around the time of Heidegger and Husserl. For a composer to write with a phenomenological awareness, it may be assumed that the inherent musical meaning must be disregarded or, at the very least, not the primary concern of the music. The French composer Erik Satie, who described his music as musique d’ameublement or ‘furniture music’, wrote a piece for piano called Vexations (den Teuling and Kok 2012) in 1893. Vexations includes a short bass theme and accompanying semitonal chords which are repeated 840 times, producing an entirely cyclical work of around eight hours long, leading the listener towards an emancipation of sonic assumption and harmonic expectation. Vexations was first performed by John Cage and a relay of pianists, including the co-founder of Velvet Underground John Cale. There is little research as to the reception of the performance, but the American musicologist Marc Thorman argues that Cage was influenced by this work, as “repetition (becomes) the main idea in Letters to Satie but Cage introduces new elements - superimposition, electronics and chance, both in the scores and in his extended performance.” (Thorman 2006) Historically, musical chronology, has grown out of a dichotomy between tension and resolution. This chronology is defined by Fred Lerdahl and Carol Krumhansl the contrast between “tensions as both sensory dissonance and cognitive dissonance or instability… (and resolution as) sensory consonance or cognitive consonance or stability.” (Lerdahl and Krumhansl 2007) In Satie’s music, although the harmonic language is not explicitly atonal (being the type of harmonic language the American musicologist Mark DeVoto refers to as “tonal chromaticism” (DeVoto, n.d.)), he quite often stays in a state of unresolved dissonance, with no explicit direction except in final cadential moments, which themselves are often sparse. A state of constant tonal chromaticism will naturally lead to an increase in the levels at which one perceives the music, as demonstrated below in Figure 1. Figure 1 – The influence of Satie’s harmonic language on levels of perception The use of tonal chromaticism generates a static harmonic plane, eradicating the tension between sensory and cognitive dissonance and consonance. The absence (or simplicity) of the musical structure, alongside an emancipation of diatonic narrative, will lead to an immobile aesthetic, inviting the listener to freely move around the sonic space rather than their attention be guided by the musical’s intrinsic narrative. Perhaps the most famous example of stasis in Satie’s compositional output is in his Trois Gymnopedie (1888). Further proof of this comes from aesthetic response research by Dale Misenhelter and John A. Lyncher. The pair tested the aesthetic response of students comparing Satie’s Trois Gymnopedie to Chopin’s more narrative-based composition Ballade No. 3 in A-flat (1841) They concluded, after a thorough Continuous Response Digital Interface (CRDI) experiment, that the students who listened to the Satie “indicated a rather flat response (whereas) results of the Chopin portion of the study group were considerably different, with substantial peaks and valleys noted across the entire time of the work that appear to roughly correspond with contrasts as related to the form, texture and dynamics of the Ballade”. (Misenhelter and Lyncher 1997) |

Archives

August 2023

All work is subject to copyright.

© Matt Geer, 2022. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed