|

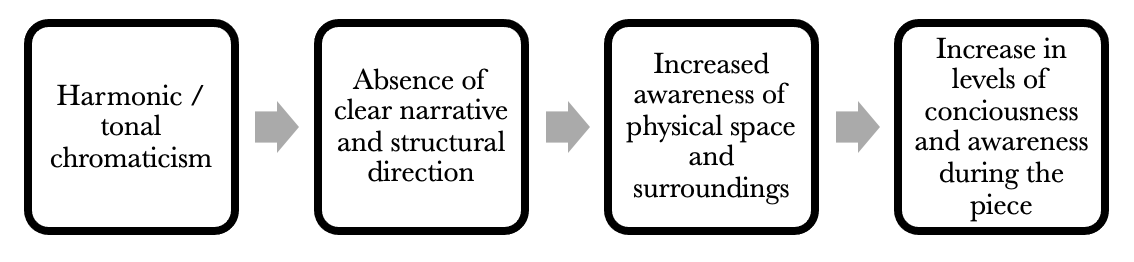

Prior to Edmund Husserl’s 1913 publication Ideen, the transcendental and idealist philosophies of Immanuel Kant onwards were centralised around independence and self-awareness. A focus on self-consciousness was also a concern of composers writing during the beginnings of music as an experimental discipline, which Jenny Gottschalk argues that “the focus (in experimental music) is ontological, on being in that collective space and what transpires in the place and time of the performance, and in the minds of those who attend”. (Gottschalk 2016) Phenomenological qualities such as temporal awareness and fluctuating attention are the primary concern of many composers today, but can be traced back to composers writing at around the time of Heidegger and Husserl. For a composer to write with a phenomenological awareness, it may be assumed that the inherent musical meaning must be disregarded or, at the very least, not the primary concern of the music. The French composer Erik Satie, who described his music as musique d’ameublement or ‘furniture music’, wrote a piece for piano called Vexations (den Teuling and Kok 2012) in 1893. Vexations includes a short bass theme and accompanying semitonal chords which are repeated 840 times, producing an entirely cyclical work of around eight hours long, leading the listener towards an emancipation of sonic assumption and harmonic expectation. Vexations was first performed by John Cage and a relay of pianists, including the co-founder of Velvet Underground John Cale. There is little research as to the reception of the performance, but the American musicologist Marc Thorman argues that Cage was influenced by this work, as “repetition (becomes) the main idea in Letters to Satie but Cage introduces new elements - superimposition, electronics and chance, both in the scores and in his extended performance.” (Thorman 2006) Historically, musical chronology, has grown out of a dichotomy between tension and resolution. This chronology is defined by Fred Lerdahl and Carol Krumhansl the contrast between “tensions as both sensory dissonance and cognitive dissonance or instability… (and resolution as) sensory consonance or cognitive consonance or stability.” (Lerdahl and Krumhansl 2007) In Satie’s music, although the harmonic language is not explicitly atonal (being the type of harmonic language the American musicologist Mark DeVoto refers to as “tonal chromaticism” (DeVoto, n.d.)), he quite often stays in a state of unresolved dissonance, with no explicit direction except in final cadential moments, which themselves are often sparse. A state of constant tonal chromaticism will naturally lead to an increase in the levels at which one perceives the music, as demonstrated below in Figure 1. Figure 1 – The influence of Satie’s harmonic language on levels of perception The use of tonal chromaticism generates a static harmonic plane, eradicating the tension between sensory and cognitive dissonance and consonance. The absence (or simplicity) of the musical structure, alongside an emancipation of diatonic narrative, will lead to an immobile aesthetic, inviting the listener to freely move around the sonic space rather than their attention be guided by the musical’s intrinsic narrative. Perhaps the most famous example of stasis in Satie’s compositional output is in his Trois Gymnopedie (1888). Further proof of this comes from aesthetic response research by Dale Misenhelter and John A. Lyncher. The pair tested the aesthetic response of students comparing Satie’s Trois Gymnopedie to Chopin’s more narrative-based composition Ballade No. 3 in A-flat (1841) They concluded, after a thorough Continuous Response Digital Interface (CRDI) experiment, that the students who listened to the Satie “indicated a rather flat response (whereas) results of the Chopin portion of the study group were considerably different, with substantial peaks and valleys noted across the entire time of the work that appear to roughly correspond with contrasts as related to the form, texture and dynamics of the Ballade”. (Misenhelter and Lyncher 1997)

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

August 2023

All work is subject to copyright.

© Matt Geer, 2022. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed